Which way, Chinese Refiner?

Heightened uncertainty about the direction of Chinese oil demand clouds its refining outlook

Before today's swirling geopolitical anxiety, several culprits were complicit in last month's stunning collapse in oil prices – looming OPEC+ policy decisions, macro fears leading to demand concerns, extreme positioning in the futures markets – but one, recent ruminations about Chinese oil demand have placed oil analysts into an introspective quandary. Long the dominant driver of global oil demand, the potential removal of that Chinese pillar throws the entire global supply/demand balance framework into disarray.

Meanwhile, in the Middle Kingdom, previous certainties about the direction of its refining system are fading with this demand ambiguity. Although China still appears committed to self-sufficiency in petrochemicals (see our previous report here), featuring large Crude-oil -to-chemicals (COTC) refineries, enthusiasm for building more traditional plants is waning. The country's previously-stated goal for reaching 20 mbpd of refining capacity is looking particularly wistful. China's goal to continue improving the efficiency and sophistication of its refining system remains undiminished, however, as it continues to cull smaller plants with more modest upgrading capabilities.

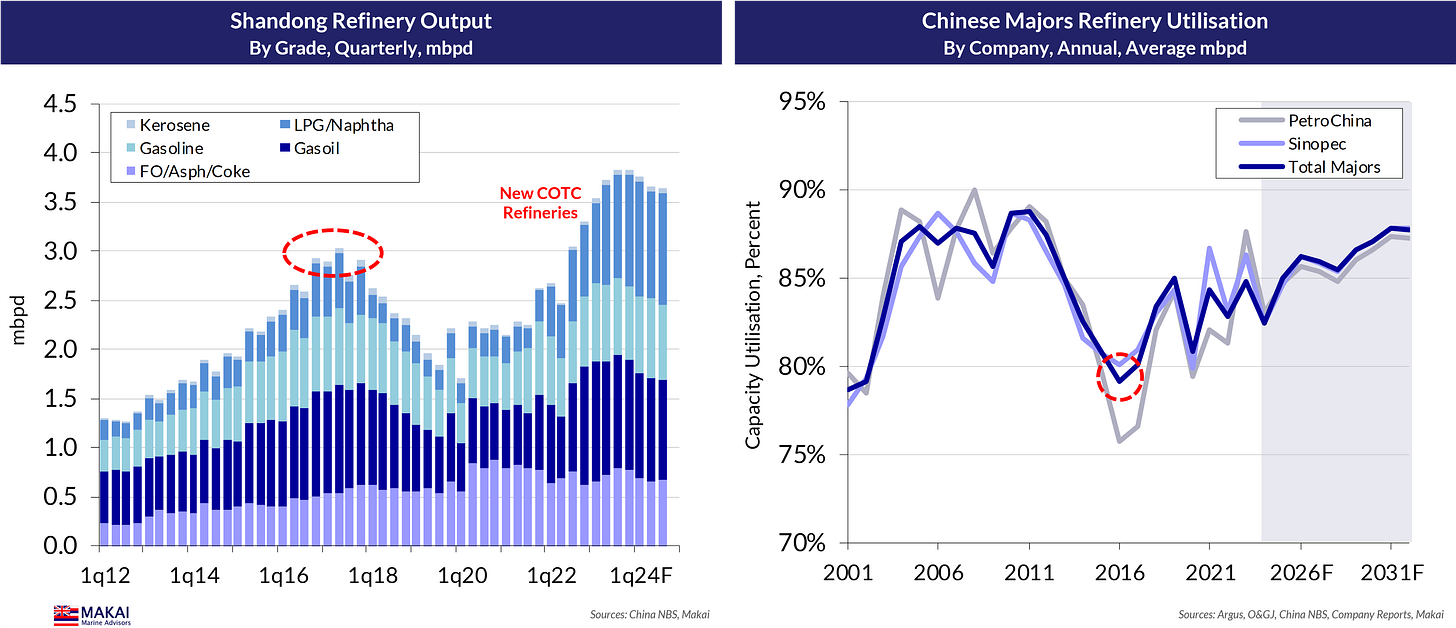

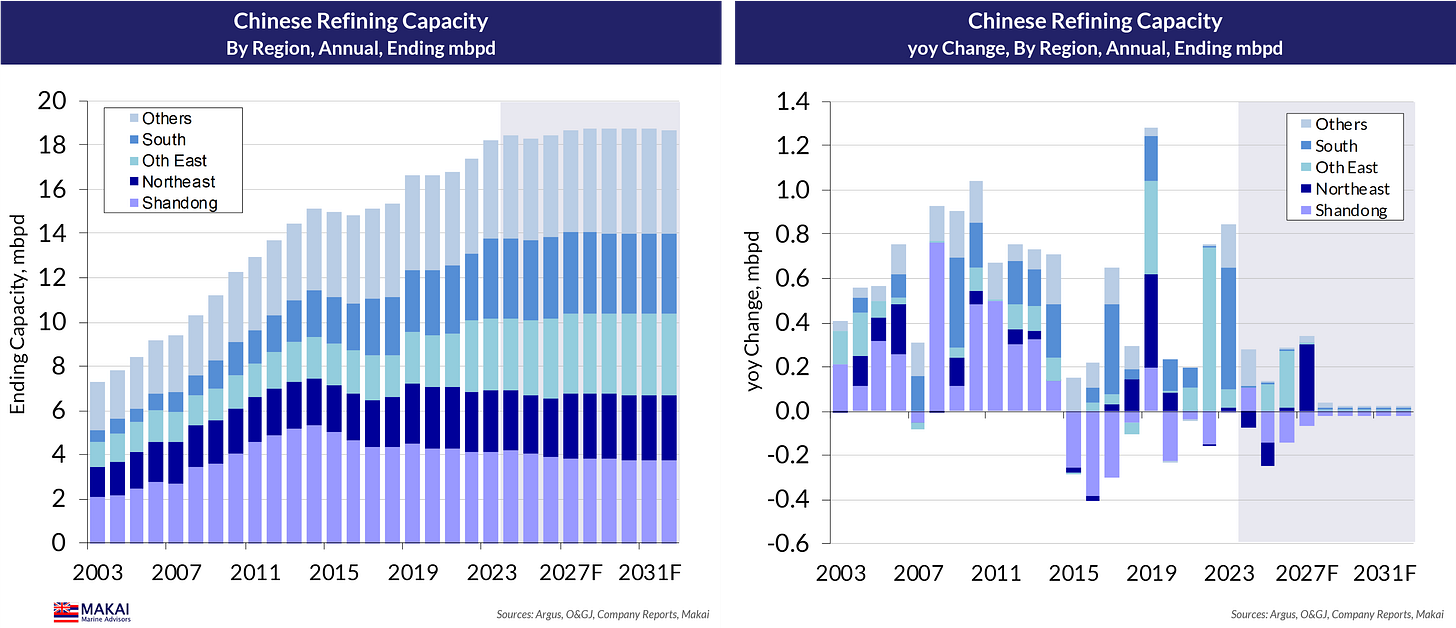

Still, the imminent flattening in the trajectory of Chinese demand growth does suggest a sharp deceleration in annual Chinese crude run growth over the next five years, to 0.2-0.3 mbpd, from the 0.6 mbpd pace pre-Covid and the monstrous 1.3 mbpd leap in 2023. For crude tanker owners, this would imply crude import growth of 0.3 mbpd in our Base Case, or the need for an uninspiring extra 7-9 VLCCs a year with a mix of Atlantic Basin and AG supply.

Let's see how the Chinese refining outlook is evolving.

Chinese oil demand: the ambiguity of peak demand

Although the penetration of EVs in Chinese car sales has been rising consistently since 2020, the passing of the 50% share mark this summer has galvanised calls for peak Chinese petrol demand. This has also sparked market speculation as to when peak Chinese total oil demand might occur.

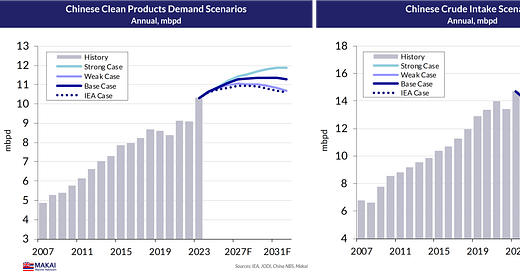

When it comes to outrageous peak demand forecasts, however, no one can compete with the IEA, whose Net Zero religious zealotry permeates its medium-term forecasts, particularly for petrol demand. The chart below highlights the divergence from our Chinese gasoline demand forecast, versus the dramatic decline foreseen by the IEA.

Trying to reverse engineer IEA forecasts is always entertaining, but for Chinese mogas demand, the implied assumptions are tortured engagements in wishful thinking. Meanwhile, we have tried to be more balanced with our model assumptions, and the resulting Base Case forecast suggests a plateau in petrol demand.

Underpinning our analysis is the assumption that Chinese car ownership levels continue to rise linearly with per capita income, and remain consistent with other Asian emerging economies.

With an anticipated increase in car scrap rates from a relatively-low 1-2% now, this implies the level of passenger car sales needed to meet these ownership levels.

Of course, the critical variables in this exercise are the level of EV penetration in sales and what share do Battery EVs (BEVs) take relative to Plug-in Hybrid EVs (PHEVs). We typically run three scenarios, as well as the IEA Case, which provides a range of potential outcomes.

We have applied a range of S-curve trajectories for the sales penetration of NEVs, or New Energy Vehicles, in Chinese terminology. The curves are consistent with some industry outlooks, while the near-term forecasts reflect the recent pace of sales gains. The IEA outlook requires a 90% NEV sales penetration by 2030.

The BEV share of NEV sales is critical to the gasoline demand outlook and the most difficult to forecast. Our near-term estimates are based upon the rate of decline in the BEV share since 2021, then assumes a stabilisation in the share. Although the Chinese government provides widespread support for BEV sales through subsidies, tax exemptions and charging infrastructure investments, the Chinese market may be facing the same rising preference for PHEVs seen in other countries. Also, Chinese manufacturers are offering more PHEV models, further encouraging their uptake.

Again, the IEA forecast requires some hefty assumptions about the BEV share. We suspect that they based their forecast in the Oil 2024 publication on a continued 60-70% share for BEVs, and now, the forecast requires a strong rebound in BEV share. This is unlikely, given consumer preferences.

Scrap rates for NEVs should remain limited, given the young age of the fleet, but ICE vehicle scrap rates should continue to grind higher from their current 1-2% levels, supported by government scrap incentives. In general, emerging markets with rapidly-growing car fleets have lower scrap rates than the 5-7% in developed markets, but the IEA forecast requires a four-fold increase in ICE scrap rates.

These moderate 2-3% scrap rates should result in gasoline-powered vehicles remaining at 51% of the passenger car fleet by 2032 (above). With improving fuel economy, petrol demand from them would decline by 14% from a 2025 peak (below).

A growing PHEV fleet, however, would add to gasoline demand, providing a consumption peak in 2027, under the Base Case. As shown below, the peak in gasoline demand varies by scenario, from 2026 (Weak Case), to 2030 (Strong), but according to the IEA, that peak is occurring now.

Those other grades

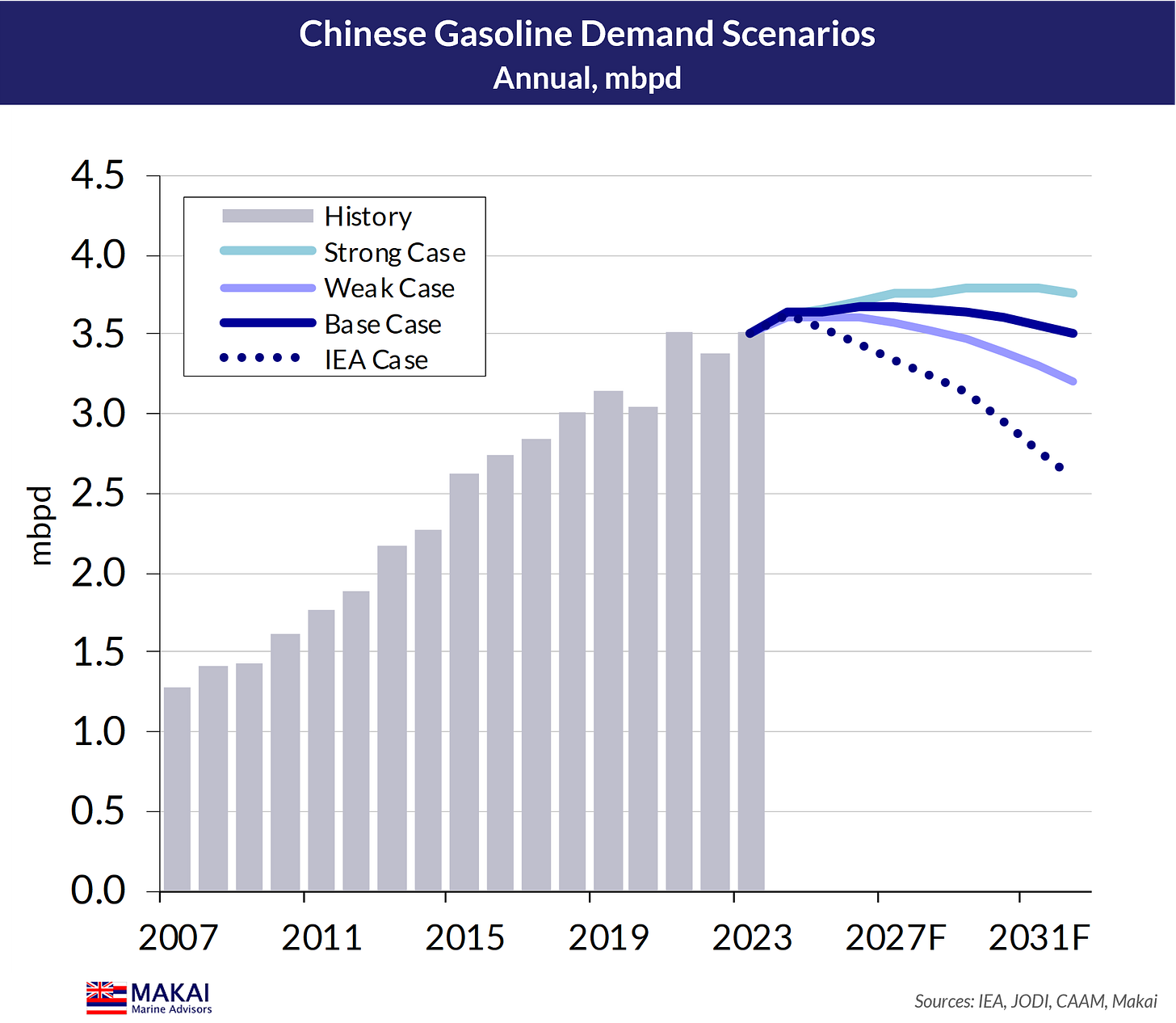

In addition to growing EV angst, a surge in LNG truck sales this year has also caught the oil market off guard, suggesting that diesel demand, already struggling from weak macro conditions, may be facing a peak sooner than expected. Even unrelenting jet fuel demand, supported by long-term household income growth, faces the threat of heavy-handed government mandates for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) use. As a whole, middle distillate demand peaks around 2030 in our Base Case.

Along with rising petchem naphtha inputs, clean product demand should plateau around 2028, while total oil demand could see a 2031 peak in the Base Case.

Of course, the problem with forecasts citing "peak demand in 20xx" is that small tweaks in the model parameters can produce peaks in any desired year, as shown in the above charts. Meanwhile, an obsession with calling for a "peak year" misses the critical point that Chinese oil demand is poised to be essentially flat after 2026, and that the global oil markets would lose their largest demand growth driver.

Refining sector response

This dynamic is not lost on the Chinese government and the domestic refining sector. Given the long lead times for refinery construction, the Chinese authorities have faced some challenging options during the past several years.

Continue to build refineries in an uncertain demand environment, and potentially endure low utilisations and weak margins as a major exporter

Slow refinery construction and potentially become a gasoline importer, without aggressive EV adoption

Apparently, the Chinese have adopted modified Option 2, by pursuing that pace of EV penetration through massive government intervention, allowing a more modest pace of refinery construction.

Structural shifts

While the Chinese refining sector grapples with the evolving demand environment, it has experienced some dramatic structural shifts during the past 20 years, while quadrupling output. The vast majority of these shifts revolve around China's privately-owned refiners, typically referred to as "Teapots", although this term is now a misnomer. They are distinct from the four state-owned enterprises (SOEs) engaged in refining: Sinopec, PetroChina (CNPC), CNOOC and Sinochem.

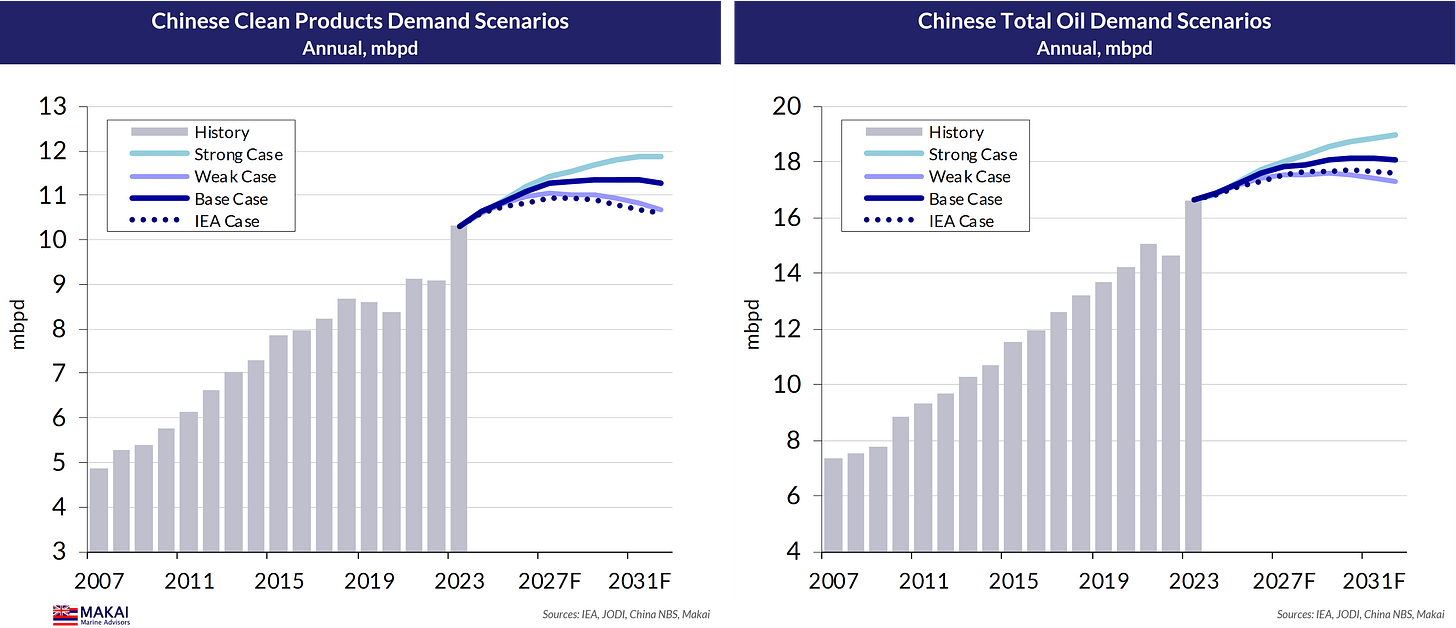

The term teapot was accurate 20 years ago, given their small scale and lack of sophistication at the time. Predominately located in the Shandong province, and without crude import quotas, they initially relied on domestic crude from the SOEs and domestic and imported fuel oil as feedstocks. With sporadic feedstock opportunities, these plant often faced low utilisations near 30% and marginal profitability.

Today, the private sector features large, world-scale refineries, typically COTC plants, such as the 800 kbpd Rongsheng Zhoushan facility (ZPC). With the SOE refiners content to hold a 70% share, the growth of these larger independent refiners is finally squeezing out the smaller, sub-scale plants.

"Finally", since China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has engaged in a multi-decade campaign to modernise the sector and to cull the smaller, less-efficient plants -- not always successfully. The smaller Shandong refineries have proven adept at dodging and adjusting to NDRC regulatory changes, as well as engaging in tax-advantaged shifts in operations, if not outright tax fraud.

For example, in 2015, the NDRC finally agreed to issue crude import quotas to the independents -- in exchange for closing units with a capacity below 40 kbpd and adhering to stricter environment regulations. The smaller independents responded by consolidating plants, adding capacity and flaunting the regs. Now armed with crude quotas, their utilisations jumped, and without export quotas, they flooded the local market, pressuring the SOE utilisations lower.

Not amused by this, the NDC revoked and reduced crude quotas, and sent tax auditors into Shandong. The cat-and-mouse games have continued for another decade, with the latest 2024 tax rulings aimed at eliminating fuel oil as a feedstock for the smaller refiners. This ruling has the potential to hit the smaller independents, but ultimately, they will succumb to the superior economics of the larger independents.

Chinese refining landscape

Their emergence is redefining the Chinese refining sector. Isolating the major independents from the smaller units, the addition of just four refineries has doubled the size of this group, including this year's Yulong start-up.

Meanwhile, the phase "Shandong independents" needs revision. Shandong once represented 80% of China independent refining capacity, at its zenith in 2014, but with the addition of larger plants in other provinces, that share is now 50%.

Within Shandong, the smaller independents are playing a smaller role, from the growth in larger refineries. This consolidation should continue, and note the loss of Sinochem capacity from three bankruptcies this year.

As with the independent sector, Shandong is playing a smaller provincial role in the context of overall Chinese refining. The impact of the NDRC regulatory mandates in 2015 is apparent in the yoy changes.

Following the significant capacity growth of the 2000s, the pace of SOE expansion has slowed, but punctuated by CNPC's 400 kbpd Jieyang start-up in 2023.

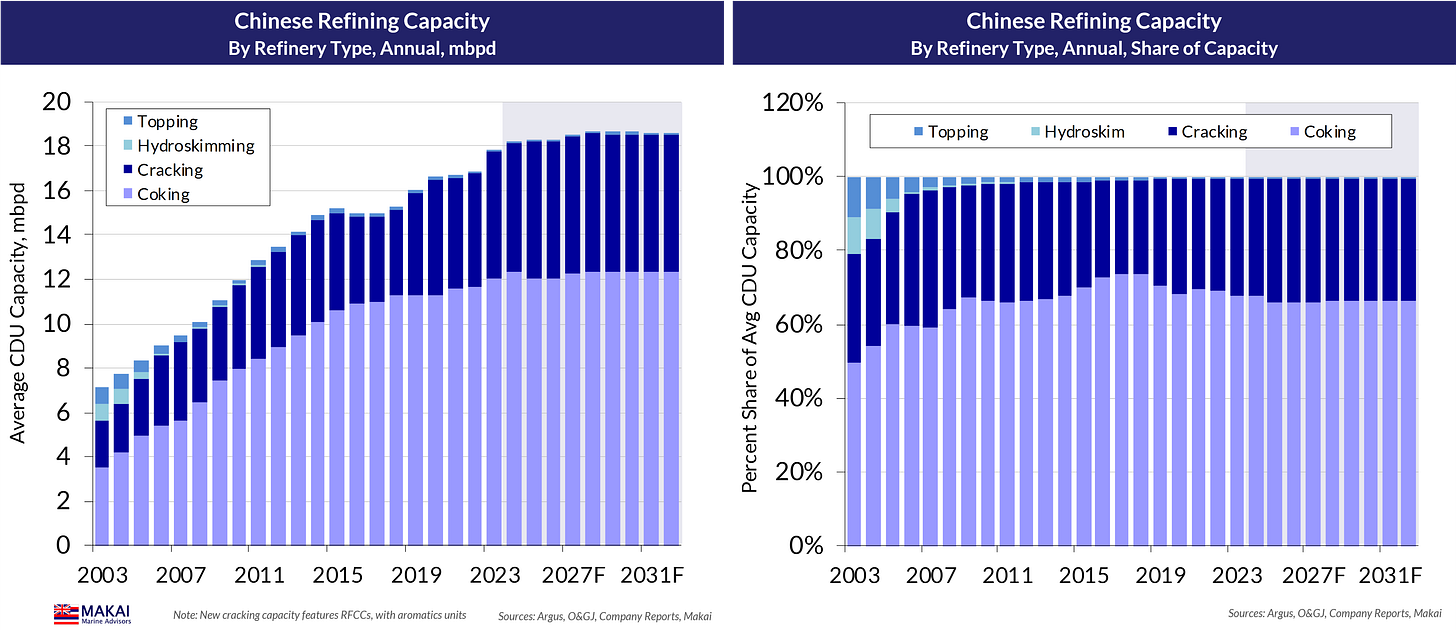

During the past 20 years, the Chinese refining system has become increasingly sophisticated and complex, with the massive addition of upgrading capacity, relative to crude distillation (CDU) capacity. Note the high concentration of cokers in Shandong prior to 2010, given the predominance of fuel oil as a feedstock.

Strong growth in Chinese diesel demand drove a sustained increase in coking refineries, which has slowed, as the product demand mix has shifted. The increase in cracking refineries reflects the use of resid FCCs in COTC facilities to accommodate olefins production in support of integrated petchem units.

Chinese refining balances

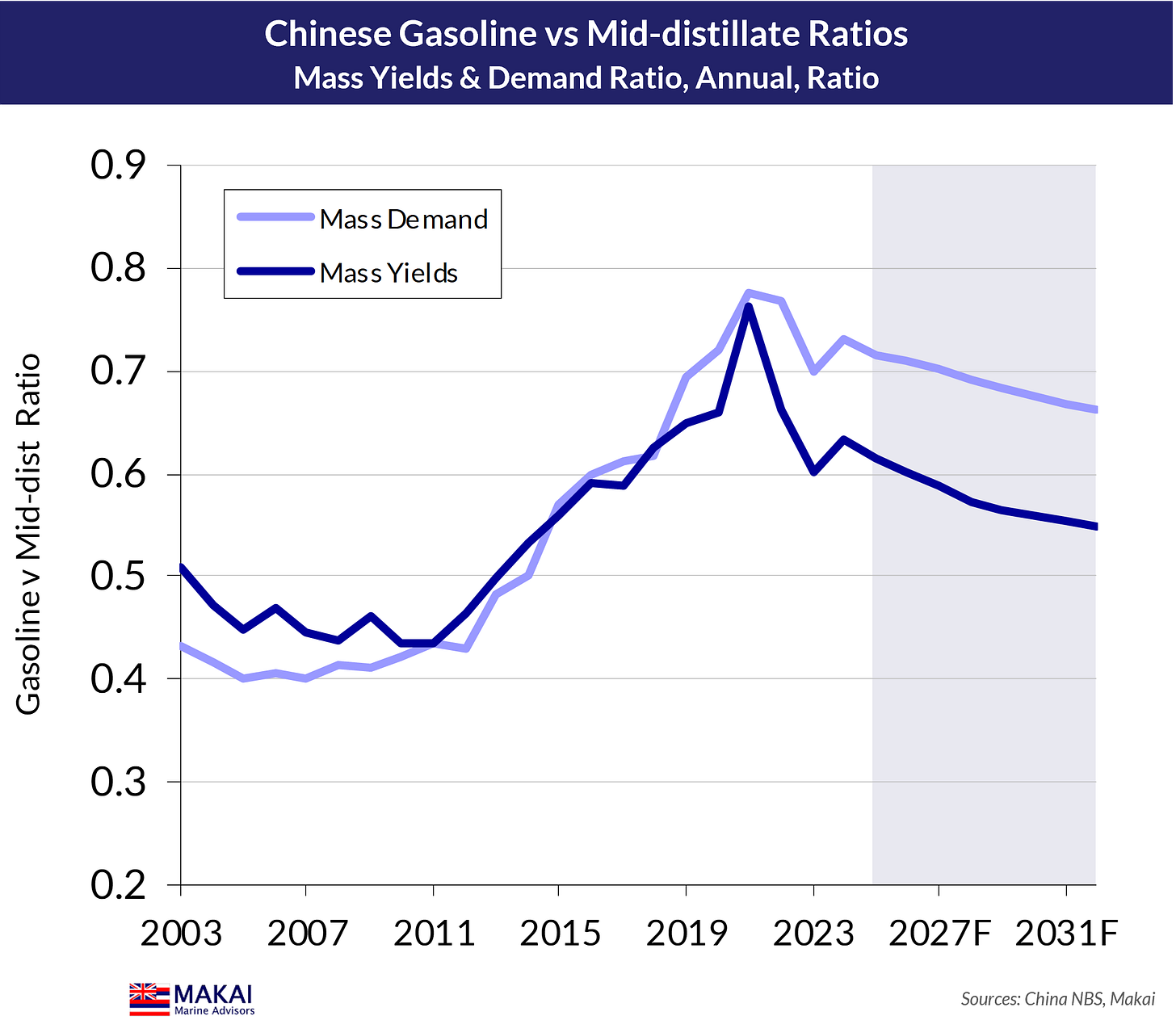

Rising jet fuel and petchem naphtha demand, while gasoline consumption plateaus and gasoil use stalls, presents meaningful challenges to the Chinese refining system in its current configuration. Earlier, the system responded to a ten-year shift in petrol demand relative to mid-distillates, and has recently reduced gasoline yields by boosting naphtha yields to meet petchem demand.

Much of this recent gasoline/naphtha reversal is structural, with the rise of COTC refineries, but dealing with this awkward product mix shift returns China to the refining capacity versus export exposure question. With 85% of China's clean product exports heading to the ASEAN region, China's ability to expand its crude intake and increase utilisations will depend upon the region's scope for absorbing additional product.

Overall, ASEAN product import needs should continue rising, suggesting room for extra Chinese exports, but this year's dip on weaker Asian demand curtailed Chinese flows and crude runs. As discussed in our earlier ASEAN report (here), the region's import needs grow at a more modest pace through 2028, on moderate refinery expansion, then accelerate.

Still, product mix is also an issue here, with Chinese exports unable to keep pace with ASEAN gasoline needs, while jet is excess to regional needs. ASEAN meets most of its petrol needs from the AG, while excess Chinese jet flows to HK, AUS/NZ, USWC and other Pacific Basin destinations. Gasoil is becoming something of a surplus product regionally, and becomes the balancing item for Chinese crude runs.

Utilisations should rebound in 2025, and if Chinese refiners keep capacity in check, would rise towards previous highs in the Base Case.

Higher Chinese demand scenarios drive higher crude runs, but IEA forecasts leave Chinese refiners with excess petrol that cannot find a home in an EV-saturated world.

Generally, higher Chinese domestic demand lowers product export availability, even with higher runs, given regional gasoil balancing, while the IEA outlooks prove bizarre in the later years.

The crude run scenarios run into the crude import cases, which benefit from declining Chinese crude production. Still, import demand growth would average 0.2-0.3 mbpd through 2029, when declining demand would take hold. Under a mix of Atlantic Basin and AG crude sources, this implies demand for 7-9 extra VLCCs per year, or 2.0-2.5 mdwt annually. The current dirty tanker orderbook stands at 42 mdwt.

Conclusion

Although the oil markets are currently transfixed by the possibility of oil infrastructure damage from an escalating Iran/Israel conflict, it was only five weeks ago that several narratives sent crude oil prices 15% lower. Narrative does always follow price, but one of those narratives -- peaking Chinese oil demand -- is still sitting uncomfortably in the oil market psyche. The IEA Chinese demand views are misguided, but sustained forces are moving that demand towards a plateau.

This leaves the Chinese authorities with some uncomfortable choices. They can continue building refining capacity and face market exposure as a major exporter in an uncertain demand environment. Alternatively, they can keep capacity in check, while continuing to cull less-efficient plants and adjusting throughput in line with regional import needs.

We view the latter option as the more-likely outcome, and with it, brings slower Chinese crude intake growth and imports.

For the balance of Asia, India has no reservations about continuing its aggressive growth in refining capacity, while ASEAN refiners will continue to increase runs though 2028. This suggests that Asian crude imports should average 0.6 mbpd of growth through that year. Of course, with much of the Russian crude largesse stabilising and a heavy AG slate, Indian crude imports would only require an additional 1 mdwt per year. With the majority of ASEAN crude demand growth located on the western fringes of the region, its tanker demand would register near 0.9 mdwt annually. Combined, Asian crude imports would require 4.0-4.5 mdwt per year.

Again, this tallies against a 42 mdwt dirty tanker orderbook, with 7 mdwt of deliveries scheduled for 2025, followed by 15 mdwt in 2026. And no, owners and the sell side are not remotely thinking in these terms.

Useful as always, thanks 🙏